Jesse’s

Intent

Jesse’s

Intent

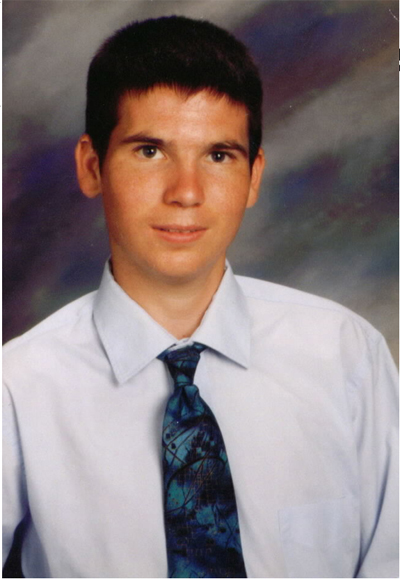

The story

of Jesse Geslinger as written by his father, Paul.

Part 2

Jesse

called us that night using his phone card. He was well, had a little

mix-up with the cabbie about which hospital to take him to. The

cabbie was cool about it though, he said. Reminded him of a scary

version of James Earl Jones. Jesse was to have more N15 testing

the following day and again on Sunday before the actual gene infusion

on Monday, September 13. Saturday was an off day and he would be

able to leave the hospital. Two of my brothers had arranged to visit

with Jess and that had put me at ease about not going. Jess had

a blast with his uncle and cousins on Saturday and a good visit

with his other uncle and aunt on Sunday. Mickie and I spoke with

Jesse every day and his spirits were good. He was apprehensive on

Sunday evening. The doctor had put him on intravenous medications

because his ammonia was elevated. I reasoned with him that these

guys knew what they were doing, that they knew more about OTC than

anybody on the planet. I didn’t talk with the doctors; it

was late. Jesse

called us that night using his phone card. He was well, had a little

mix-up with the cabbie about which hospital to take him to. The

cabbie was cool about it though, he said. Reminded him of a scary

version of James Earl Jones. Jesse was to have more N15 testing

the following day and again on Sunday before the actual gene infusion

on Monday, September 13. Saturday was an off day and he would be

able to leave the hospital. Two of my brothers had arranged to visit

with Jess and that had put me at ease about not going. Jess had

a blast with his uncle and cousins on Saturday and a good visit

with his other uncle and aunt on Sunday. Mickie and I spoke with

Jesse every day and his spirits were good. He was apprehensive on

Sunday evening. The doctor had put him on intravenous medications

because his ammonia was elevated. I reasoned with him that these

guys knew what they were doing, that they knew more about OTC than

anybody on the planet. I didn’t talk with the doctors; it

was late.

I received a call from the principal investigator on Monday just after they infused Jesse. He explained that everything went well and that Jesse would return to his room in a few hours. I discussed the infusion and how the vector did its job. He didn’t like the word invade when I explained what I thought the virus did to the liver cells. He explained that if they could affect about one percent of Jesse’s cells, that they would get the results they desired. Mickie and I spoke with Jesse later that evening. He had the expected fever and was not feeling well. I told Jesse to hang in there, that I loved him. He responded, “I love you too, dad.” Mickie got the same kind of goodbye. Little did we know it was our last. I awoke very early Tuesday morning and went to work. I received a mid-morning call from the doctor asking if Jesse had a history of jaundice. I told him not since he was first born. He explained that Jesse was jaundiced and a bit disoriented. I said, “That’s a liver function, isn’t it?” He replied that it was and that they would keep me posted. I was alarmed and worried. My ex-wife, Pattie, happened to call about twenty minutes later and I told her what was going on and she reminded me that Jesse had jaundice for three weeks at birth. I called the hospital back with that information and got somebody who was apparently typing every word I said. That seemed very unusual to me. I didn’t hear from the doctors again until mid-afternoon. The other principal investigator, the OTC expert, called and said Jesse's condition was worsening, that his blood ammonia was rising and that he was in trouble. When I asked if I should get on a plane, he said to wait, that they were running another test. He called back an hour and a half later and Jesse’s ammonia had doubled to 250 micromoles per deciliter. I told him I was on a plane and would be there in the morning.

They got Jesse’s breathing under control and his blood ph returned to normal. The clotting disorder was described as improving and the OTC expert returned to Washington, D.C. by mid-afternoon. I started relaxing, believing Jesse’s condition to be improving. My brother and his wife arrived at the hospital around 5:30 p.m. and we went out to dinner. When I returned I found Jesse in a different intensive care ward. As I sat watching his monitors I noted his oxygen content dropping. The nurse saw me noticing and asked me to wait outside, explaining that the doctors were returning to examine Jesse. At 10:30 p.m. the doctor explained to me that Jesse’s lungs were failing, that they were unable to oxygenate his blood even on 100% oxygen. I said: “Whoa, don’t you have some sort of artificial lung.” He thought about it for a moment and said yes, that he would need to call in the specialist to see if Jesse was a candidate. I told him to get on it. I called my wife and told her to get on a plane immediately. At 1:00 a.m. the specialist and the principal investigator indicated that Jesse had about a 10% chance of survival on his own and 50% with the artificial lung, the ECMO unit. Hooking up the unit would involve inserting a large catheter into the jugular to get a large enough blood supply. I said, “50% is better than 10, let’s do it.” It seemed like forever for them to even get the ECMO unit ready. Jesse’s oxygen level was crashing. At 3:00 a.m. as they were about to hook Jesse up, the specialist rushed into the waiting room to tell me that Jesse was in crisis and rushed back to work on him. The next few hours were really tough. I didn’t know anything. Anguish, despair, every emotion imaginable went through me. At 5:00 a.m. the specialist came to see me and said they had the ECMO working but that they had a major leak, that the doctor literally had his finger on the leak. I quipped that I was a bit of a plumber; maybe that’s what they needed. He returned to work on Jesse and I began to worry for my wife. Hurricane Floyd had made landfall in North Carolina at 3:00 a.m. and was heading toward Philly. At 7:00 a.m. I entered through the disabled double doors into the intensive care area and after noting four people still working on Jesse and another half dozen observing, approached the nurse’s station to get them to see if my wife would get in ok. They agreed to check and asked if I would like a chaplain. I’m a pretty tough guy, but it was time for spiritual help. The chaplain, a man a few years younger than me, was called in to help me. At this point I was trying to contact my family, my mother, to get emotional support. A hospital staffer was very helpful in that respect.

By mid-morning six of my siblings with their spouses had arrived. Mickie’s plane just got in before they closed the airport and she arrived in the pouring rain by taxi at the hospital. We weren’t able to see Jesse until after noon. The OTC expert was stuck on a train disabled between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore by the hurricane. The two doctors on site described Jesse’s condition as very grave; that whatever reaction his body was having would have to subside before he could recover. His lungs were severely damaged and if he survived it would be a very lengthy recovery. They had needed to use more than ten units of blood in hooking him up. When we finally got to see Jesse, he was bloated beyond recognition. He was so bloated that his eyes and ears were swelled shut, even extrudying the wax out of his ears. The only way to be sure it was Jesse was the battle scar with his dad on his elbow and the tattoo on his right calf. My siblings were shaken to the core. Mickie touched him ever so gently and lovingly, our hearts nearly breaking. With the hurricane closing in and threatening to close the bridges home, my siblings left by late afternoon. My sister and her husband stayed to take us to dinner and drive us exhausted to our hotel. After sleeping for an hour, I arose and felt compelled to return to see Jesse. Leaving Mickie a note I walked the half-mile back to the hospital in a light rain. Hurricane Floyd had skirted Philly and was heading out to sea. I found Jesse’s condition no better. I noted blood in his urine. I thought, “How can anybody survive this?!” I said a quiet goodbye to Jesse and returned to the hotel at about 11:30 p.m. I found Mickie preparing to join me. I described Jesse’s condition as no different and returned to bed. Mickie went out walking for a few hours. In the morning we arrived at 8:00 a.m. at Jesse’s room. A new nurse indicated that the doctors wished to speak to us in an hour or so about why they should continue with their efforts. We went to have breakfast at the hospital cafeteria. I knew and told Mickie we should be prepared for a funeral. She wanted to believe he would get well. The principal investigators were there when we returned. They told us that Jesse had suffered irreparable brain damage and that his vital organs were all shutting down. They wanted to shut off life support. They left us alone for a few minutes and we collapsed into each other. On their return, I told them that I wanted to bring my family in and have a brief service for Jesse prior to ending his life. Then I told them that they would be doing a complete autopsy to determine why Jesse had died, that this should not have happened. While waiting for my siblings, moments of anger toward the doctors would sweep over me. I would say to myself, “No, they couldn’t have seen this.” I went so far as to tell the OTC expert that I didn’t blame them, that I would never file a lawsuit. Little did I know what they really knew. Seven of my siblings and their spouses and one of my nieces were present for the brief ceremony for Jesse… more for us at this point. About ten of the hospital staff were present. I had all the monitors shut off in his room. Leaning over Jesse, I turned and declared to everyone present that Jesse was a hero. After the chaplain’s final prayer, I signaled the doctors. The specialist clamped off Jesse’s blood flow to the ECMO machine and shut off the ventilator. After the longest minute of my life, the principal investigator stepped in and I removed my hand from Jesse’s chest. After listening with a stethoscope for a moment he said,”Goodbye, Jesse, we’ll figure this out.” Not a dry eye all around. This kid died about as pure as it gets. I was humbled beyond words. My kid had just shown me what it was really all about. I still feel that way. At the time of Jesse’s death, I believed he had died of the very remote possibility that the doctors had theorized but not seen in their animal data. I supported them for months. My first clue that something was amiss was in early November, 1999, six weeks after his death. One of the principal investigators, the one who had infused the vector, was in Tucson to help me hike and spread Jesse’s ashes on a local mountain top. At a meeting with the University of Arizona researcher who had initially reviewed the otc study for the government in 1995, I was told in the principal investigator’s presence that monkeys had died in the pre-clinical work. The Tucson researcher in private also expressed his misgivings to me regarding the FDA’s oversight efforts and indicated that I should seek out the minutes of the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee meetings of 1995. Following that meeting the principal investigator from Penn was quick to point out to me that they had changed the original vector that had killed monkeys to make it much safer. His explanation at that time satisfied me and I continued my support for their work.

|

A week later I discovered the minutes that the UofA researcher had asked me to seek out. As far back as 1995 the FDA and the NIH were working on a web database to disseminate information on adverse reactions in gene therapy. In the June 1995 minutes of the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee meeting, I discovered that the effort to create this Gene Therapy Information Network was announced by the FDA representative to be over. The RAC, indignant because it knew the importance of this database in protecting the participants of research, demanded an explanation. The FDA representative's candid response that “my superiors answer to industry” told me volumes. There had been a report in the newspapers at that time that Schering-Plough had stamped adverse effects in a similar gene transfer study as proprietary and had withheld dissemination of that adverse information. I was incensed at what that meant regarding the oversight of the work. I felt at the time that the Penn researchers had been blindsided by that non-dissemination of information and informed them of what I had discovered. In late November 1999, the head researcher, Dr. James Wilson, traveled to my home in Tucson, AZ where I met him for the first time, some two month’s after Jesse’s death. He was there to present the findings of Jesse’s autopsy. My first question to him while sitting on my back porch was, “What is you financial position in this?” His response was that he was an unpaid consultant to the biotech company, Genovo, behind the research effort. Being naïve, I accepted his word and continued my support for him and his work. I decided to attend the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee meeting in early December 1999 in Bethesda, Maryland where all the experts were to discuss my son’s death. Dr. Wilson had asked me to fly in a day early to do a morale boost for his 250 person Institute at Penn. At first hesitant, I agreed to do it. I had received a phone message from a director within the FDA and returned her call while waiting in Phoenix for my connecting flight to Philly. In that phone call I explained to her in no uncertain terms about my discovery of the lapses within the FDA and that I intended to expose the FDA’s faulty oversight efforts at the RAC meeting. While at Penn the following day I was informed by a tearful Dr. Wilson late in the afternoon that the FDA had just issued a press release blaming his team with Jesse’s death. It seemed I had touched a very sensitive nerve. The following day I rose very early and drove three hours to Bethesda for the three day RAC meeting. It wasn’t until that three-day meeting that I discovered that there was never any efficacy in humans. I had believed this was working based on my conversations with the OTC expert and that is principally why I had defended them and their institution for so long. These men could not go in front of their peers and say this was working. I also discovered that the research team had violated the protocol in multiple ways, had not adequately reported serious adverse events in the other patients prior to Jesse, and had withheld vital information from the FDA on adverse reactions in animals. Now realizing that everyone had failed Jesse, I sought legal counsel. In uncovering the truth of what happened to Jesse, we found some very major problems in the informed consent process:

These are but a few examples of how our medical research system is rife with conflict of interest. Jesse's case is far more a symptom of a dysfunctional system than an isolated incident of research run amok. We filed a lawsuit a year and a day after Jesse’s death against the three principal investigators, their institutions, and their review boards. I wanted to include our government for its failures but it has immunity. We held to our guns and settled our case six weeks later out of court. The quickness of that settlement should tell you how much the other side wanted this to go away. On February 10, 2002 the FDA issued a scathing letter that reads more like an indictment of Dr. Wilson indicating that it was in the final stages of disbarring him from ever again being able to conduct research on human beings. Dr. Wilson stepped down as head of the Institute for Human Gene Therapy effective July 1, 2002. To date neither Dr. Wilson nor the University of Pennsylvania have accepted any responsibility for Jesse’s death. We have never received a public apology from anyone responsible for what occurred.

|

Links:

Washington Post News Articles: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/health/specials/genetherapy/gelsingercase/

H. Stewart Parker’s Feb. 2000 testimony: http://www.senate.gov/~labor/hearings/feb00hrg/020200wt/frist0202/gelsing/kast/patter/fda-zoon/verma/walters/parker/parker.htm

June 1995 RAC minutes: http://www4.od.nih.gov/oba/rac/minutes/6-8-9-95.htm

FDA’s Feb. 2002 letter to Dr. Wilson: http://www.fda.gov/foi/nooh/Wilson.pdf

Website Design by aGenius

It’s

a very helpless feeling knowing your kid is in serious trouble

and you are a continent away. My plane was delayed out of Tucson

but got into Philly at 8:00 a.m. Arriving at the hospital at 8:30

a.m. I immediately went to find Jesse. As I entered thru the double

doors into surgical intensive care I noted a lot of activity in

the first room I passed. I waited at the nurse’s station

for perhaps a minute before announcing who I was. Immediately,

both principal investigators approached me and asked to talk to

me in a private conference room. They explained that Jesse was

on a ventilator and in a coma, that his ammonia had peaked at

393 micromoles per deciliter (that’s at least ten times

a normal reading, but only slightly above the highest reading

Jesse had ever had) and that they were just completing dialysis

and had his level down under 70. They explained that he was having

a blood-clotting problem and that because he was breathing above

the ventilator and hyperventilating his blood ph was too high.

They wanted to induce a deeper coma to allow the ventilator to

breath for him. I gave my ok and went in to see my son. After

dressing in scrubs, gloves and a mask because of the isolation

requirement I tried to see if I could rouse my boy. Not a twitch,

nothing. I was very worried, especially when the neurologist expressed

her concern at the way his eyes were downcast… not a good

sign, she said. When the intensivist told me that the clotting

problem was going to be a real battle, I grew even more concerned.

I called and talked to my wife, crying and afraid for Jesse. It

was at least as bad as the previous December, only this time they

had been in his liver. I would keep her posted.

It’s

a very helpless feeling knowing your kid is in serious trouble

and you are a continent away. My plane was delayed out of Tucson

but got into Philly at 8:00 a.m. Arriving at the hospital at 8:30

a.m. I immediately went to find Jesse. As I entered thru the double

doors into surgical intensive care I noted a lot of activity in

the first room I passed. I waited at the nurse’s station

for perhaps a minute before announcing who I was. Immediately,

both principal investigators approached me and asked to talk to

me in a private conference room. They explained that Jesse was

on a ventilator and in a coma, that his ammonia had peaked at

393 micromoles per deciliter (that’s at least ten times

a normal reading, but only slightly above the highest reading

Jesse had ever had) and that they were just completing dialysis

and had his level down under 70. They explained that he was having

a blood-clotting problem and that because he was breathing above

the ventilator and hyperventilating his blood ph was too high.

They wanted to induce a deeper coma to allow the ventilator to

breath for him. I gave my ok and went in to see my son. After

dressing in scrubs, gloves and a mask because of the isolation

requirement I tried to see if I could rouse my boy. Not a twitch,

nothing. I was very worried, especially when the neurologist expressed

her concern at the way his eyes were downcast… not a good

sign, she said. When the intensivist told me that the clotting

problem was going to be a real battle, I grew even more concerned.

I called and talked to my wife, crying and afraid for Jesse. It

was at least as bad as the previous December, only this time they

had been in his liver. I would keep her posted.

My

own son has shown me the way to lead my own life and for that

I am so very grateful. I have watched our system struggle to come

to grips with what is wrong with the protection of human beings

in medical research. What is wrong is that a growing ambitious

minority of researchers and institutions have compromised their

ethics for profits and prestige, mostly as a result of industry’s

inappropriate financial influence on them and our government.

I still support our need for clinical trials, but with this caution:

Informed consent is only possible if all facets of the research

endeavor are ethical and in the open. Because of the secretive

and conflicting influences on clinical research, the average research

subject has little hope of understanding and giving truly informed

consent. All research subjects really want is to be able to trust

the system. If we can somehow get that system to apply Jesse's

Intent... not for recognition and not for money, but only to help...

then research will get all it wants and more; they'll get research

right and have a real prosperity, one they never imagined possible.

Until that happens I am so very grateful that we had a legal recourse

that enabled us to draw attention to the problems currently inherent

in clinical research.

My

own son has shown me the way to lead my own life and for that

I am so very grateful. I have watched our system struggle to come

to grips with what is wrong with the protection of human beings

in medical research. What is wrong is that a growing ambitious

minority of researchers and institutions have compromised their

ethics for profits and prestige, mostly as a result of industry’s

inappropriate financial influence on them and our government.

I still support our need for clinical trials, but with this caution:

Informed consent is only possible if all facets of the research

endeavor are ethical and in the open. Because of the secretive

and conflicting influences on clinical research, the average research

subject has little hope of understanding and giving truly informed

consent. All research subjects really want is to be able to trust

the system. If we can somehow get that system to apply Jesse's

Intent... not for recognition and not for money, but only to help...

then research will get all it wants and more; they'll get research

right and have a real prosperity, one they never imagined possible.

Until that happens I am so very grateful that we had a legal recourse

that enabled us to draw attention to the problems currently inherent

in clinical research.